Cinq cents plaques obsessionnelles et chimiques par Léon Aymonier, pharmacien et photographe amateur: 1892-1934. « Le photographe du Châtelard nous a légué l’ensemble de ses contemporains, comme il nous a légué les morts : éternisés dans le moindre détail. Et si nous nous arrêtons parfois sur un regard, sur un visage, sur une fillette comparable à celles de Lewis Carroll, nous sommes surtout sensibles aux détails (… qui) nous parlent des catégories sociales, d’une époque, d’un lieu et inventent la possible reconstitution d’une fiction littéraire aux côtés de l’histoire ». (C. Caujolle, Libération)

OUVRAGE ÉPUISÉ

Lire la préface de John Berger

Léon Aymonier, pharmacien et photographe, en potache.

UN UNIQUE REGARD

Il y a beaucoup de manières de lire cette remarquable collection de photographies des habitants du Châtelard-en-Bauges prises entre 1892 et 1934. D’abord et avant tout, elle représente un document historique. Pour les gens de la région en question, ce document historique peut être aussi un document personnel. Nous ne pouvons que supposer les motivations du photographe-pharmacien, Aymonier, quand il insistait tellement systématiquement à prendre des photographies de tous ceux qu’il connaissait ou pouvait rencontrer, qu’ils soient vivants ou sur leur lit de mort. Il me semble que ces motivations étaient probablement ce que nous nommerions aujourd’hui ethnographique. Il voulait probablement établir une sorte de typologie des habitants de la petite ville. De la même manière, il est possible de regarder chacune des photographies comme la biographie du photographié — même si très peu de cette biographie est connu. A ce moment, l’historique et le psychologique se rejoignent. Bien plus même, la première lecture historique peut être subdivisée en informations se rapportant aux événements locaux, à la condition de la paysannerie française de cette époque, à l’économie de la région, à la distinction entre les classes sociales, à la mystérieuse relation qui existait entre le photographe et le photographié.

La découverte de cette collection a déjà provoqué un certain matériel de recherche. Cette recherche constitue une contribution à l’histoire locale et l’on doit se souvenir ici que, jusqu’il y a peu, l’histoire des régions rurales en France était une catégorie de l’histoire qui ne trouvait pas habituellement sa place dans les livres d’histoire. Nous sommes donc dans le domaine de ce qui fut généralement ignoré. Il y a là beaucoup de découvertes qui sont encore à faire et l’on ne peut parvenir à ces découvertes que par une recherche patiente et systématique. A ce travail précieux et nécessaire je ne peux moi-même malheureusement rien ajouter. Je regarde ces photographies comme un étranger à part entière. Et pourtant, en tant que tel, je peux être conscient de ce qu’il y a d’intrinsèquement mystérieux à propos d’elles.

J’écris ces lignes durant la semaine de mardi gras. Dans notre village de Haute-Savoie, c’est le moment où une partie des villageois — et non seulement les enfants — mettent des habits qui ne sont pas les leurs d’habitude et portent des masques. Ils sortent déguisés dans le village. Le village devient une sorte de théâtre. Et les acteurs, quoique bien connus de tout le monde, sont difficiles et même impossibles à reconnaître. L’efficacité de ce théâtre repose probablement sur deux principes: que tout le monde connaît la personne derrière le masque, lorsqu’elle est démasquée : et qu’il y a une loi paysanne de l’hospitalité qui veut que les étrangers, s’il n’y a pas de raison évidente de les soupçonner, doivent être accueillis dans les maisons. Et ainsi, les bandes des connus/inconnus font leur tour du village et sont invitées à prendre un verre ou à recevoir des œufs. Tout ceci avec de nombreux rires, plaisanteries et espiègleries. Il y a aussi, pourtant, une autre dimension moins évidente à ce théâtre traditionnel. Les costumes que l’on porte sont pour la plupart vieux, ils appartiennent au passé. Les masques sont modernes, mais dans leur fixité il y a quelque chose qui ressemble à l’esprit des absents ou des morts. Le théâtre est pour une part un théâtre des revenants. Les disparus, les morts, les inconnus, les oubliés, les presque-oubliés et les familiers font une réapparition. Cette réapparition est sous le signe du Carnaval. Elle est accompagnée de rires, paillardises, exagérations, caricatures. C’est comme si, pour un instant, l’éternel est un jeu, le jeu éternel.

Je décris ceci maintenant parce que ces photographies, tout en se rapportant au passé, aux morts, familiers en un sens, inconnus à bien des égards, possèdent un esprit et évoquent une expérience qui sont l’exact opposé de ceux du Carnaval. Pendant le Carnaval, les morts offrent un peu de leur libération aux vivants. Les deux se rencontrent dans le jeu éternel. Dans ces photographies, il n’y a pas trace du moindre jeu, de la moindre libération ou fête. Ici le passé réapparaît comme prisonnier.

Qu’est ce qui faisait cette prison? Quelques-unes des réponses sont des lieux communs. Les conditions économiques de la région, la dureté impossible à idéaliser de la vie paysanne, la profondeur du réalisme paysan face à la nécessité, la reconnaissance des frustrations comme inévitables. La fureur et la passivité. Il y a une autre réponse partielle et moins générale: la prison de la situation dans laquelle la plupart des photographiés doivent se soumettre aux exigences du pharmacien tout-puissant; ceux-ci assis, ceux-là debout suivant sa décision, tous spécimens pour sa recherche « objective » dans la typologie humaine dont il est l’investigateur privilégié.

Pourtant, toutes ces réponses données, il y a quelque chose de mystérieux qui subsiste et ce mystère rejoint celui de tous les prisonniers et de tous les morts. Le mystère de ce violent interrogatoire que les photographiés nous font subir, à nous les lecteurs de ce livre qui ne sommes pas prisonniers et qui sommes encore vivants.

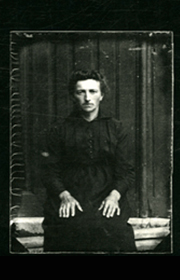

Maintes fois on retrouve dans l’expression du visage qui nous scrute un regard commun, presque identique. Ce peut être le visage d’un enfant encore à l’école du village, le visage d’un vétéran des deux guerres, le visage d’une vieille fille, le visage, effronté, d’une jeune femme, dans la fleur de l’âge, le visage d’un conquérant local ou celui d’un perdant-né. Comment expliquer la parenté de ces regards perçants?

Bien sûr un visiteur au Châtelard à l’époque en question, un jour ou un soir bien précis — supposons même que c’était mardi gras — n’aurait pas eu conscience d’une même qualité partagée par tous les visages qu’il observait. Cette qualité a à voir avec la distorsion photographique. Elle a à voir avec la personnalité du pharmacien, avec la manière systématique et plutôt malhabile dont il prenait des photographies, avec la relation autoritaire qu’il établissait avec les photographiés, avec les réactions des photographiés face à cette mystérieuse machine qui saisissait leurs apparences et les conservait pour le futur, avec le mystère de l’instant artificiellement isolé et figé.

Pourtant si ces photographies ne nous parlaient que de l’acte d’être photographié, elles ne nous hanteraient pas comme elles le font.

Quelque chose d’autre est à l’œuvre. Nous regardons ceux qui ont disparu. Ils ne sont pas revenus partager leurs plaisanteries avec nous au moment du Carnaval. A cet instant où nous les voyons, ils n’étaient pas morts (les images de lits de mort sont à part), ils n’étaient pas morts, et pourtant ils prévoyaient déjà tout. Ce qu’ils prévoyaient, c’était l’inévitable, pourtant en regardant l’inévitable, ils ne pouvaient contenir la fureur, non, la tenace obstination de leurs espoirs. Espoirs encore intacts, ou espoirs abandonnés encore en mémoire.

Je ne sais pas exactement ce qui arrivait à chaque fois que le pharmacien installait ses modèles en face de l’appareil. Je suis tenté de dire appareil diabolique, car dans l’uniformité de ce que ses photographies montrent, il y a quelque chose du diabolique. Ou, plus précisément, quelque chose de l’infernal. Malgré toute leur banalité, ces photographies sortent de l’enfer. Les condamnés que Dante décrit étaient avides des nouvelles du monde qu’ils avaient quitté, ils voulaient encore savoir ce qui s’y passait; d’une manière très inattendue, cela les concernait encore. Et il en est ainsi, même plus directement encore, de ces photographies.

Dans ces photographies de vivants, maintenant disparus, maintenant une part du passé, comme leurs vêtements que l’on sort au Carnaval, nous voyons les yeux d’un espoir furieux dirigé vers l’avenir où quelque chose d’autre de ce qu’ils ont vécu existe au moins comme un désir. Aujourd’hui leur regard nous interroge parce que, sans jamais pouvoir nous imaginer tels que nous sommes, ils le dirigeaient vers notre temps. Dire leur espoir utopique serait non seulement faux, ce serait aussi nous rendre les choses trop faciles. Ces photographies nous imposent le devoir d’être hantés. Ceux qui nous hantent font une seule exigence : une exigence simple à définir mais difficile à satisfaire l’exigence de reconnaissance.

John Berger

Read the John Berger's forword

Léon Aymonier, chemist and photographer.

TOWARD US

There are many ways of reading this remarkable collection of photographs of the inhabitants of Le Châtelard-en-Bauges taken between 1892 and 1934. First and foremost it represents an historical document. For the people of the region in question this historical document may also be a personal one. We can only guess at the motives of the chemistphotographer, Aymonier, when, during those years, he so systematically insisted on taking photographs of everyone he knew or came to know, whether alive or on their death-beds. It seems to me that these motives were probably what we would now call ethnographic. Probably he wanted to establish a kind of typology of the inhabitants of the small town. Equally, it is possible to look at each single photograph in terms of the biography — even if very little is known of that biography of the photographed. At this moment the historical and the psychological come together. Furthermore even the first historical reading can be subdivided into information relating to local events, to the condition of the French peasantry at that period, to the economy of the region, to the distinction between social classes, to the mysterious relation existing between the photographer and the photographed.

The discovery of this collection bas already provoked a certain body of research. This research is a contribution to local history, and one should remember here that, until recently, local rural history in France was a category of history that did not usually enter the history books. We are in the domaine of what was generally ignored. There are many dicoveries still to be made here and these discoveries can only be arrived at through patient and systematic research. To this valuable and necessary work I myself can unfortunately add nothing. I look at these photographs as a complete outsider. Yet, as such, I may be aware of what is intrinsically mysterious about them.

I am writing these lines during the week of mardi gras. In our village in the Haute-Savoie this is the moment when some of the villagers — and not only the children amongst them — put on clothes which are not their habitual ones and wear masks. They go out into the village disguised. The village becomes a kind of theatre. And the actors, although familiar to everyone, are hard or even impossible to recognise. The effectiveness of this theatre probably depends upon two principles: that everyone knows the person behind the mask when urimasked: and that there is a rural law of hospitality that strangers, if there is no evident reason to suspect them, should be welcomed into the house. And so, the bands of the known/unknown make their tour of the village and are invited in to drink a glass, or be given eggs. All this to much laughter, joking and questioning. There is also, however, another, less obvious, dimension to this traditional theatre. The costumes worn are mostly old, they belong to the past. The masks are modern, but in their fixity there is something which resembles the spirit of the absent or dead. The theatre is partly a theatre of ghosts. The departed, the dead, the unknown, the forgotten, the half-remembered and the familiar make a reappearance. This reappearance is under the sign of Carnival; it is accompanied by laughter, ribaldry, exaggeration, caricature. It is as if, for a moment, the eternal is a joke, the joke eternal.

I describe this now because these photographs, whilst also being concerned with the past, the dead in some ways familiar and in many ways unknown, possess a spirit and evoke an experience which are the exact opposite to those of Carnival. In Carnival the dead offer some of their liberation to the living. The two meet in the eternal joke. In these photographs there is no trace of any joke, liberation or celebration. Here the past re-appears as prisoner.

What made the prison? Some of the answers are commonplace. The economic conditions of the region, the unidealisable harshness of peasant life, the profundity of peasant realism in face of necessity, the recognition of frustrations as inevitable. The fury and the passivity. There is another partial and less general answer: the prison of the situation in which most of the photographed had to submit to the demand of the powerful chemist that they should stand or sit there as specimens for his « objective » research into the human typology, of which he was the priviledged investigator.

Yet when all the answers have been given, there is something mysterious which remains, and this mystery is closely associated with both prisoners and the dead. The mystery of the photographed’s fierce interrogation of us, the readers of this book, who are net prisoners and who are still alive.

Time and time again one finds in the expression of the face that is regarding us a common, almost identical, look. It may be the face of a boy still at the village school, the face of a veteran of two wars, the face of an old spinster, the face of a young woman, brazen, on the threshold of her life, the face of a local conqueror, or that of one born into defeat. How te explain the community of this piercing look?

Of course a visiter to Le Châtelard during the epoch in question, on a particular day or evening — let us even suppose that it was mardi gras — would net have been aware of a quality shared by all the faces that he or she observed. This quality is to do with photographie distortion. It is to do with the character of the chemist, with the systematie and rather unskillful way in which. he took photographs, with his authoritarian relation to the photographed, with the reactions of the photographed to that mysterious machine which was going to seize their appearances and preserve them for the future, with the mystery of the instant artificially isolated and preserved. Yet if these photographs only told us something about the act of being photographed they would net haunt us in the way that they do.

Something else is at work. We are looking at those who have disappeared. They have net come back te share their jokes with us at the moment of Carnival. At the moment, at which we are seeing them, they were not dead (apart from the deathbed images), they were not dead, and yet they already foresaw all. What they were foreseeing was the inevitable, yet in looking at inevitable they could net suppress the fury, no, the dogged obstinacy of their hopes. Hopes which were still intact, or abandoned hopes which. were still remembered.

I do not know exactly what happened each time the chemist set up his sitters in front of the camera. I am tempted to say diabolic camera, for in the consistency of what his photographs show, there is something of the diabolic. Or, more accurately, something of the infernal. For all their banality, these photographs are reminiscent of the inferno. The condemned, whom Dante described, were avid for news of the world they had left, they still wanted to know what was happening now; unexpectedly it still concerned them. And se it is, even more directly, with these photographs.

In these photographs of the living, now departed, now part of the past, like their clothes taken out at Carnival, we see the eyes of a furious hope directed towards the future where something other than what they have lived, exists at least as an idea. Today their look interrogates us because they, without ever imagining us as we are, directed their look towards our time. To call their hope utopian would be not only false, it would also make it too easy for us. These photographs impose upon us the duty of being haunted. Those who haunt, make one demand: a demand simple to define but hard to meet: the demand of recognition.

John Berger.

OUVRAGE ÉPUISÉ